The Iconography of Outrage

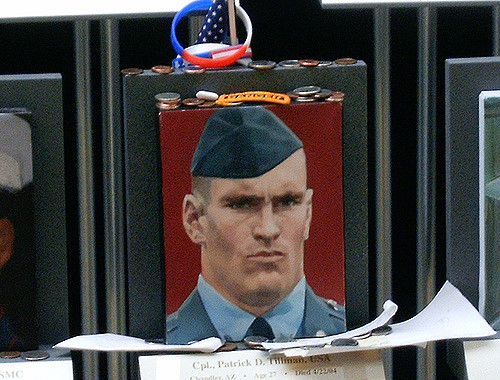

Some people upset with Nike’s 30th anniversary “Just Do It” campaign featuring Colin Kaepernick, in their outrage, replaced Kaepernick’s image with that of Pat Tillman. In doing so, however, they most likely are politicizing Tillman’s sacrifice and service in a way he wouldn’t have endorsed. (Photo Credit: Bethany J. Brady/Flickr/CC BY 2.0)

Chances are someone you know has given up on using Facebook, Twitter, or both because he or she regards it as a haven for discord and stupidity. Personally, my biggest gripe is there are too many Nazis and far-righters milling about, but I sympathize with the position of those who have forsaken these outlets. After all, when you write a post about how whiteness is a distinction that merits no pride, and the first comment you receive is from someone you don’t know living across the country who suggests you should pick a fight with a “real white man” and find out, you tend to want to roll your eyes, throw your computer in the garbage, and call it a day.

Suffice it to say, though, that outrage isn’t just plentiful in the Twitterverse and within the blogosphere—it may as well be a type of currency for social media. In the era of President Donald Trump, it seemingly has spiked the way bitcoin’s price shot up amid its initial surge.

Liberals are upset with the Trump presidency because, well, it’s a shit show. Conservatives are upset with liberals who are upset with Trump. Progressives are upset with liberals for hewing too close to center. Ultra-conservatives are upset with conservatives for spending too much on war and other things. Trump, on top of all this, tweets in frustration all the time, and most of us will be damned if we can figure out why exactly. In all, it’s an exhausting maelstrom of deprecation and fury.

The demand for outrage-inducing content is such that, in the haste to provide it, people, works of art, etc. can be exploited as icons of this outrage. Often times, this purpose will be served against the express wishes of those whose images or work is being usurped.

A recent salient example of this was when Mollie Tibbetts’ murder at the hands of an undocumented immigrant became a rallying cry for border security and immigration enforcement. Trump and other xenophobes like him once again began beating the drum of immigration “reform,” sounding a call for building a wall and for addressing the alleged flood of dangerous immigrants crossing into the United States.

One person who isn’t joining in with pitchforks and torches, meanwhile, is Ron Tibbetts, Mollie’s father, echoing a position other family members have espoused. In an op-ed piece in the Des Moines Register, he urged people not to “distort her death to advance racist views.” From the piece:

Ten days ago, we learned that Mollie would not be coming home. Shattered, my family set out to celebrate Mollie’s extraordinary life and chose to share our sorrow in private. At the outset, politicians and pundits used Mollie’s death to promote various political agendas. We appealed to them and they graciously stopped. For that, we are grateful.

Sadly, others have ignored our request. They have instead chosen to callously distort and corrupt Mollie’s tragic death to advance a cause she vehemently opposed. I encourage the debate on immigration; there is great merit in its reasonable outcome. But do not appropriate Mollie’s soul in advancing views she believed were profoundly racist. The act grievously extends the crime that stole Mollie from our family and is, to quote Donald Trump Jr., “heartless” and “despicable.”

Make no mistake, Mollie was my daughter and my best friend. At her eulogy, I said Mollie was nobody’s victim. Nor is she a pawn in others’ debate. She may not be able to speak for herself, but I can and will. Please leave us out of your debate. Allow us to grieve in privacy and with dignity. At long last, show some decency. On behalf of my family and Mollie’s memory, I’m imploring you to stop.

It is hard to imagine the heartbreak I would feel having a member of my immediate family die in such a gruesome way, and on top of this, to have people like Candace Owens invoke the racist trope of the white woman attacked by a man of color to further their agenda amid my grief. For that matter, I’m not sure I wouldn’t be angry at the individual who killed someone I love.

Keeping this in mind, I consider it a testament of Ron Tibbetts’ character and of Mollie’s that he would argue against messages of division and hate in the aftermath of learning that she had died. As such, his appeals to not “knowingly foment discord among races” as a “disgrace to our flag” and to “build bridges, not walls” carry much weight. As does his notion that the divisive rhetoric of Trump et al. does not leadership make.

“The Lonesome Death of Mollie Tibbetts” isn’t the only event in recent memory by which Americans, flying a flag of pseudo-patriotism, have taken an idea and run with it despite the explicit objection of its originator. The forthcoming movie First Man, which premiered at the Venice Film Festival, has garnered criticism for not showing the planting of the flag on the moon as part of Apollo 11, a perceived slight against America about which Buzz Aldrin helped kindle outrage. The movie reportedly focuses on Neil Armstrong’s personal journey leading up to the moonwalk, and on that walk, the visit to Little West Crater.

As Neil’s sons Rick and Mark Armstrong have interceded to emphasize, though they believe otherwise, the famed astronaut did not consider himself an “American hero,” a point actor Ryan Gosling, who stars in the film, also stressed. Thus, they defend director Damien Chazelle’s choice. Chazelle himself also explained that he wanted to portray the events of the Apollo 11 moon landing from a different perspective, highlighting the humanity behind Armstrong’s experience and the universality of his achievement. One small step for a man, and one giant leap for mankind, no? Besides, as Armstrong’s sons and others have reasoned, most people nitpicking First Man haven’t actually seen it to tear it asunder.

Then there’s the whole matter of Colin Kaepernick as the face of Nike’s 30th-anniversary advertisement for their “Just Do It” campaign. The print ad, which shows Kaepernick’s face up close and personal, features the tagline, “Believe in something. Even if it means sacrificing everything.” As self-styled arbiters of patriotism and what is good and right would aver, however, Kaepernick hasn’t sacrificed anything, and featuring a non-patriot like him is grounds for divorce.

Consequently, the hashtag #NikeBoycott was trending on Labor Day and into Tuesday, replete with videos of indignant Nike owners burning their sneakers and other apparel, cutting/ripping the telltale “swooshes” out of their clothing, or otherwise vowing to never shop Nike again. I suppose on some level I appreciate their enthusiasm, though I submit there are any number of reasons why this is folly, including:

- First of all, if you never planned on buying Nike products in the first place, don’t front like your “boycott” means anything. It’s like people who complained about the Starbucks red nondenominational “holiday” cup controversy. Come on—you know y’all were only getting your coffee from Dunkin’ Donuts.

- Assuming you did actually buy Nike sneakers and apparel, burning things doesn’t take the money back. As far as the company is concerned, you can eat the shoes when you’re done with them. The transaction is done.

- Though it seems like a lost point by now, Colin Kaepernick consulted Nate Boyer, a former long snapper in the NFL and U.S. Army Green Beret, about how to protest respectfully. They eventually decided on kneeling rather than sitting as a sort of compromise, evoking the image of the serviceperson kneeling at the grave of a fallen comrade. At any rate, it’s not America or the military that Kaepernick and others have protested—it’s the treatment of people of color at the hands of law enforcement, the criminal justice system, and other rigged institutions.

- A more meaningful boycott directed at Nike would be recognizing the company’s questionable commitment to worker rights here and abroad over the past few decades, including more recent allegations of a corporate culture that discriminates against women. Just saying.

- As I’m sure numerous veterans would agree, regardless of what you think about Kaepernick and his playing ability, fighting overseas for inalienable human rights just to see players deprived of the right to protest—that is, able to enjoy fewer freedoms—does not indicate progress.

The financial fallout from Nike’s taking a stand, of course, still needs to be measured. There’s also the notion that aligning with Colin Kaepernick will ruffle feathers of NFL executives and team owners. Still, one reasons Nike would not make such a potentially controversial move without knowing what it was doing, or at least figuring it was a gamble worth taking.

Going back to social media and expression of outrage, people unhappy about Nike’s decision to celebrate a figure in Kaepernick they perceive to be a spoiled rich athlete who doesn’t know the meaning of the word sacrifice also have been active in creating and sharing parodies of Nike’s advertisement with the late Pat Tillman, another NFL player/serviceperson, swapped in for Kaepernick. While Tillman is certainly worth the admiration, it appears doubtful he would want his image used in this way.

In fact, as many would suggest, based on his political views, it’s Kaepernick he would support, not the other way around. Marie Tillman, Pat’s wife, while not specifically endorsing player protests, nonetheless publicly rebuked Trump for retweeting a post using her husband’s image. As she put it, “The very action of self expression and the freedom to speak from one’s heart—no matter those views—is what Pat and so many other Americans have given their lives for. Even if they don’t always agree with those views.” As with Ron Tibbetts’s pleas not to exploit or capitalize his daughter’s death, Marie’s desire not to see her husband’s sacrifice and service politicized is one worth honoring.

There’s any number of examples of people’s art and memories being used without their permission (assuming they can give it) despite requests to the contrary. Recently, Aerosmith frontman Steven Tyler sent a cease-and-desist letter to President Trump warning him not to use his (Tyler’s) music without his (Tyler’s) permission at his (Trump’s) political rallies. As Tyler insists, this is strictly about copyright protection—not about politics. As Trump insists, he already has the rights to use Aerosmith’s songs. If I’m believing one or the other, I’ll opt for the one who isn’t a serial liar, cheater, predator, and fraud, but you may do with these examples as you wish.

The larger point here, however, is that in the zeal for sparking outrage about political and social issues, there too frequently seems to be a failure to appreciate context—if not a blatant disregard for it. Mollie Tibbetts didn’t believe in an immigration policy which vilifies Latinx immigrants and other people of color. Neil Armstrong, in all likelihood, wouldn’t have balked at choosing not to show the planting of the U.S. flag on the moon. Pat Tillman probably would’ve backed the ability of Colin Kaepernick and other NFL players to protest during the playing of the National Anthem.

In all cases, a politically-motivated counternarrative threatens to derail meaningful discussion on the underlying subject matter. The outrage builds, as does the mistrust. The few issues upon which we disagree potentially overshadow the larger consensus we share on important topics. Sadly, this also seems to be the way many representatives of the major political parties like it.

I’ve highlighted examples in which people of a conservative mindset have co-opted other people’s memories and works amid their expression of anger and resentment. This is not to say, mind you, that there aren’t occurrences on the other end of the political spectrum.

Not long ago, actor Peter Dinklage had to intervene to defray a controversy surrounding his casting as Hervé Villechaize in a forthcoming biopic about the late actor and painter. The charge was that this casting was a case of Hollywood “whitewashing.” As Dinklage explained in an interview, however, Villechaize is not Asian, as some people believe or claim, but suffered from a particular form of dwarfism that explains why they might assume this ethnicity. From the interview:

There’s this term “whitewashing.” I completely understand that. But Hervé wasn’t Filipino. Dwarfism manifests physically in many different ways. I have a very different type of dwarfism than Hervé had. I’ve met his brother and other members of his family. He was French, and of German and English descent. So it’s strange these people are saying he’s Filipino. They kind of don’t have any information. I don’t want to step on anybody’s toes or sense of justice because I feel the exact same way when there’s some weird racial profile. But these people think they’re doing the right thing politically and morally and it’s actually getting flipped because what they’re doing is judging and assuming what he is ethnically based on his looks alone. He has a very unique face and people have to be very careful about this stuff. This [movie] isn’t Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Personally, I would never do that, and I haven’t done that, because he wasn’t. People are jumping to conclusions based on a man’s appearance alone and that saddens me.

Jumping to conclusions—on the Internet? Well, I never! Dinklage seems to take this in stride along the lines of folks meaning well, but not necessarily being well informed. In this instance, the error is fairly innocuous, but the rush to judgment in today’s climate of information sharing can have serious consequences. There’s a lesson here, no matter what your political inclinations.

As for the Nike/Colin Kaepernick business which Donald Trump may very well be tweeting about right now, Drew Magary, writing for GQ, insists that something is “hopelessly broken” when people feel compelled to champion the company synonymous with the swoosh for taking a stand. He writes:

Corporations already control so much in America that people are compelled—happy, even—to depend on them as beacons of social change, because they are now the ONLY possible drivers of it. I shouldn’t need Nike to get police departments to stop being violent and corrupt. Making decent shoes is hard enough for them, you know what I mean? But I’m forced to applaud their efforts here only because I live in a world where people cannot effect anywhere near the level of change that a billion-dollar corporation can. The social compact of this nation was meant to be between its citizens, but brands have essentially hijacked that compact, driving all meaningful conversation within. A great many brands have performed a great many acts of evil thanks to this. Others have talked up a big game while still being evil (that’s you, Silicon Valley). Only rarely do brands use their ownership of the social compact for good and genuine ends, and even then it accomplishes far less than what actual PEOPLE could accomplish if they had that compact to themselves once more. Politically speaking, one Colin Kaepernick ought to be worth a million Nikes.

Instead, as Magary tells it, “we live in a country where causes only to get to see daylight if they have a sponsor attached.” It’s a particularly bad phenomenon because corporations like Nike exist for their own benefit and have no “obligation to society.” Thus, if we need an athletic apparel company to lecture us on the virtues of sacrifice and of protesting police brutality, or if we need a pizza company to fill in potholes that municipalities can’t or won’t address, you know we’re in pretty bad shape.

While we contemplate our eroding civic virtue and crumbling infrastructure—a contemplation none too heartening, at that—we might also consider what we can do to end the “internet outrage cycle,” as Spencer Kornhaber, staff writer at The Atlantic, put it. Certainly, much as discretion may be deemed the better part of valor, discretion about what to post or tweet and whether to do so seems fundamental to limiting the reactionary culture of outrage, and outrage about others’ outrage that plagues much of interaction on contentious topics. Besides, while we’re dabbling in truisms, if one doesn’t have anything nice to say, perhaps one shouldn’t say anything at all.

Social media giants like Facebook and Twitter aren’t going anywhere anytime soon, and their ability to organize for meritorious purposes is too profound to ignore. If we’re going to use them constructively, we will need to resist the iconography of outrage, specifically that which distorts images and people to serve a new agenda. At a time when ownership of creative works can get lost in the ability to share them, and when public figures can become buried under an avalanche of negativity, it’s best to do our homework and to pick our battles when choosing a cause to fight for.