Coronavirus, Rioting, and the Privatization of Morality

(Benjamin Studebaker) A short while ago, we were making political demands on our states, of various kinds. Some of us wanted our governments to do more to stop the spread of the virus and save lives. Some of us wanted our governments to provide more aid, more economic stimulus. But over the last few weeks, we stopped making political demands. We started looking at each other. As governments began re-opening their economies, they tried to make it our responsibility to stop the virus.

You are supposed to social distance. You are supposed to wear a mask. In most places, none of this is required by law. In those jurisdictions where the advice has been incorporated into the law, it’s only nominally enforced. But you’re supposed to feel a moral obligation to do these things, and if you don’t do them people will shame you. They’ll yell at you, and maybe they’ll try to use social media to get you fired from your job.

The guidelines aren’t enforced by the state–they’re enforced by the people around you. The state doesn’t take responsibility for this informal interpersonal coercion, but it tacitly encourages it. When we’re fighting with each other about whether we should wear masks, we aren’t making demands on the state. If we’re all too busy playing police officer with each other, we won’t have the bandwidth to hold the government to account.

In modern society, we hold politics and morality to be two distinct things. If something is political, it’s the state’s responsibility. If something is moral, it becomes your job to take care of it. The political is associated with the public sphere, and the moral is associated with the private. It wasn’t always like this. Plato and Aristotle believed that the cities were ultimately responsible for ensuring the citizens become virtuous people and lead virtuous lives. For the Greeks, it was impossible to maintain a good city if the citizens weren’t good, and therefore the morality of the citizens was a public matter. Politics and morality were intertwined in a virtuous circle.

Modern philosophers began to break this relationship apart. For Montesquieu, it was unrealistic to expect citizens to ever possess virtue at scale. Virtue was just too hard to get. Montesquieu thought people were morally pretty useless, and political institutions should be designed with this in mind. He made an argument for separation of powers on this basis–ambition checks ambition, and even if all the parts of the state are corrupt, none can dominate the others.

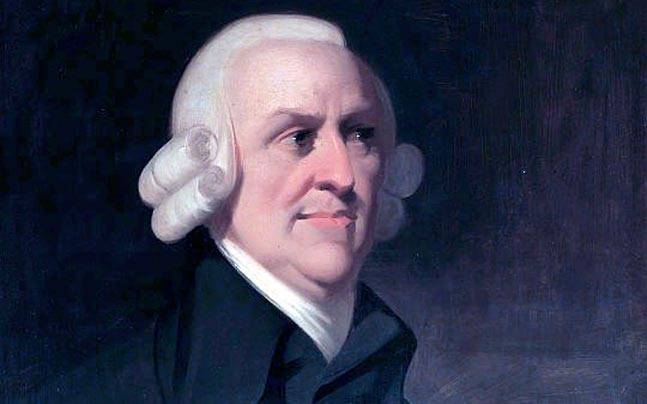

Once it became possible to imagine a political system operating apart from morality, theorists began designing moral systems that stood apart from politics. Adam Smith famously wrote two very different books–The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments. For Smith, markets only work properly when the people who participate in them are virtuous. But Smith doesn’t go into great detail about how the population is meant to acquire the virtue necessary for markets to work. Smith explains what he thinks virtue needs to do–it needs to enable us to get our moral sentiments to align with those of an imagined impartial third party observer–but he never tells us how we’re meant to develop the virtues necessary to do this. Smith describes the state in a relatively minimalist way. It’s clear that the state isn’t going to do the work of giving us the virtues necessary to generate the sentiments we require to sustainably participate in markets.

But Smith doesn’t seem to see this as a problem. Why? It’s not an oversight. Smith simply thinks that morality can be secured in the private sphere. Instead of having the state nurture virtue in its citizens, the citizens will develop their moral capacities in private, through personal journeys and participation in churches and other civil society organizations.

Smith is able to take this position because Smith is a liberal, and as a liberal he thinks that individuals have agency, that they can construct themselves and that therefore they can be held responsible for the kind of people they become.

This is not the way ancient people thought about politics and morality, and it’s not the way Marxists think about it either. Marxists think our moral beliefs stem from our position in the class structure, and therefore from our position in the economic system. For Marxists, embracing capitalism means embracing the kinds of morality that capitalist roles generate.

The Greeks focused on how different kinds of cities create different kinds of people. The Marxists focus on how different systems of political-economy perform the same role. For both the Marxists and the Greeks, our moral beliefs do not form of their own accord in a detached, insulated private sphere. What liberals call “private” is really just the cultural consequences of that which is public.

Because liberal states draw a line between public and private, between politics and morality, they can depoliticise issues by moralising them, by pushing them into the private sphere. In this way, the liberal state avoids collective responsibility for conditions, instead pushing its citizens to take personal responsibility for them. I like to call this “responsibilisation”. The liberal state “responsibilises” us, to prevent us from holding it responsible.

That is what is going on with coronavirus. We aren’t talking anymore about the big political questions. We aren’t talking about what the state should be doing. We’re talking about what each one of us should do, individually. In the last couple weeks, the United Kingdom became obsessed with an obscure minister by the name of Dominic Cummings. Cummings violated the guidelines, and this kicked off a storm of demands that Cummings be forced to resign. Criticising Cummings seems like a form of political action, but it’s not. When the British criticise Cummings, they think they are criticising the government, but they aren’t talking about what the government ought to be doing different at the level of policy. They are instead directing moral outrage at a particular person, and in so doing generating further private morality discourses around the question of what individual citizens should be doing. In this way, the conversation now treats the state’s behavior as a given. Instead of asking more from the state, the British are reduced to making demands on each other. Different British people feel different ways about Cummings, morally and aesthetically, and the debate quickly devolves into which private sentiments are aesthetically compelling or revolting. The whole thing turns into a big culture war, with no political stakes. It divides the British people, preventing them from uniting to demand anything.

In the United States, the riots have recently taken on a similar flavor. Once violence erupted, Americans stopped arguing about what they want the government to do differently. Instead, we began having an argument about whether violence is morally acceptable, about whether it’s aesthetically appealing. From there, the discourse devolved further into a discussion about whether various individual commentators’ moral and aesthetic feelings about violence are themselves morally and aesthetically acceptable and appealing. There is now a furious competition among the people who make the discourse for a living to have the “right” feelings about rioting. They think they are doing politics, but the possibility of the state taking any form of meaningful action in response to the protests recedes further each day. With every day that passes, the discussion moves further from a critique of the state’s policies and institutions, toward a superficial cultural discussion about whether we have the right feelings about the riots as individuals. We are now already more interested in our own reaction to the riots than we are in the state’s reaction.

When we fight among ourselves, we pose no threat to the state. Making an issue that could be political into a cultural question about morality and aesthetics enables the state to kick it into the long grass. The louder we fight with each other, the less the state hears us. By the time the state returns to the conversation, we are so exhausted by the fight that its offer of law and order becomes seductive. The state is able to buy our compliance by offering us the bare minimum of security against one another. The political becomes a means of rescuing us from the futility of the moral.

And why is the moral futile? Because the Greeks and the Marxists are right–there will never be any moral progress without political and economic progress. If we are to change, the system must change first. We can only change it when we do politics, and the system is designed to stop us from doing it, to push us again and again into the private, into the moral, into the cultural realm. The more angry and upset we are, the more vulnerable we are, the easier it is to turn us on each other and push us out of the political. The moral is the space where we can have the catharsis of judging another individual. The political is the space where we must confront our own impotence and weakness in the face of the power of the rich and well-connected. Given the choice, the psychologically vulnerable will always choose catharsis over the long, hard road to win power, and so the private will always be an effective means of protecting an increasingly decrepit public realm.