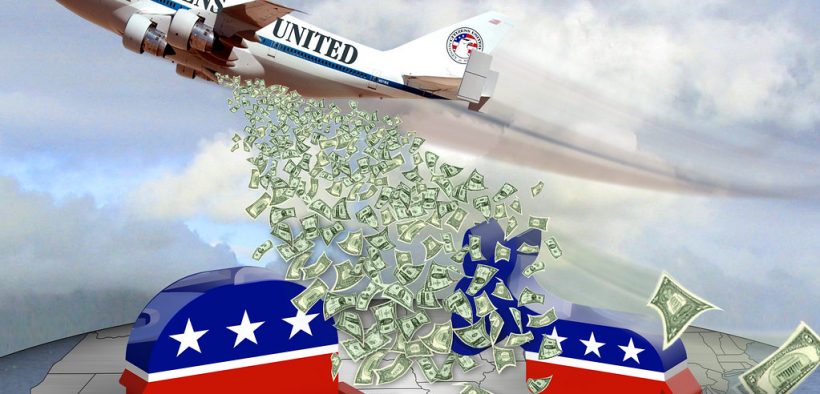

Corporate Cash Leaking Into Democratic Campaigns Despite ‘No-Corporate-PAC’ Pledge

“I won’t take money from the banker, the realtors or the hotel, but I will take money from their trade association? That’s hypocrisy.”

(By Camille Erickson, Center for Responsive Politics) More than 50 Democratic congressional candidates have lined up behind the call to boycott corporate PAC money in the name of campaign finance reform. By eschewing money from big business, candidates hope to mobilize a mighty army of small donors and kick corrupt money out of electoral politics.

But first quarter FEC filings reveal that while the majority stayed true to their word, some of the self-declared “no-corporate-PAC” candidates took money from big businesses and special interests.

Meet the Candidates

Many of the candidates on board the “no-corporate-PAC” train still welcome money from cooperatives or trade associations, even if they have ties to big business. The Center for Responsive Politics considers trade association PACs and cooperative PACs to be “business PACs” given the dues they receive from big businesses with a stake in influential industries.

Rep. Cindy Axne (D-Iowa) pocketed $2,500 from the dairy giant cooperative Land O’Lakes PAC this past quarter. And then there’s Rep. Lori Trahan (D-Mass.), who accepted $1,500 from Food Marketing Institute, a PAC that receives money from Safeway, Walmart and Coca-Cola.

Axne and Trahan did not respond to requests for comment.

Trahan also accepted $1,000 from the law firm Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough, and joined the ranks of several other “no-corporate-PAC” congress members who accepted money from law firms’ PACs.

Reps. Raul Grijalva (D-Ariz.) and Mark Pocan (D-Wis.) received $2,000 and $1,500 respectively from the law firm Foley & Lardner LLP PAC this year. A spokesman for Pocan’s campaign said the contribution was acceptable because the law firm, as a partnership and not a corporation, does not report itself as a corporate PAC in FEC filings.

Rep. Susan Wild (D-Pa.) accepted $1,000 from the law firm K&L Gates LLP. Reps. Mike Levin (D-Calif.), David Cicilline (D-R.I.) and Lucy McBath (D-Ga.) also received contributions from law firms last quarter.

These campaigns are following End Citizens United’s no-corporate-PAC standards. The organization notes that corporate PACs are by far the biggest contributors in the PAC field, making them difficult to pass up.

“The decision by so many candidates to refuse corporate PAC money changed the conversation in Washington and led directly to the House passing the most sweeping package of democracy reforms since Watergate,” said Patrick Burgwinkle, End Citizens United communications director, referring to the Democrats’ HR 1, an extensive reform bill meant in part to reduce the influence of money in politics.

But a deeper dive into candidates’ filings uncovers the ways money from corporations and big business can still trickle into progressive campaigns.

“I won’t take money from the banker, the realtors or the hotel, but I will take money from their trade association? That’s hypocrisy,” said Dr. Steven Billet, director of the legislative affairs program at George Washington University. “The money in those organizations comes from the bankers and the realtors.”

Wild accepted $5,000 from the American Hospital Association, a trade association PAC that is funded by and lobbies on behalf of both private and public hospitals, as did Axne and Rep. Andy Kim (D-N.J.).

Rep. T.J. Cox (D-Calif.) received $23,500 from 11 business PACs, including the National Association of Realtors PAC, which receives donations from Keller Williams Realty and Century 21 Signature Properties. He also received numerous contributions from groups representing agricultural interests.

In a statement, Cox’s campaign said the California representative “is proud to have won the closest election in the country last year without the support of corporate PACs, and as the representative from the number one agriculture district in the number one agriculture state, is proud to have the backing of the agriculture community as he fights for the Central Valley in Washington.”

Grijalva also received money from the National Indian Gaming Association, but said in a statement that he stands committed to campaign finance reform and taking corrupt money out of campaigns. Grijalva said he has “high standards” for the money he takes from organizations. He “welcomes support from PACs that advocate for his shared legislative priorities,” his campaign said in a statement. “Protecting the sovereignty and welfare of Indian tribes in his district and around the country is one such shared priority.”

Several candidates also accepted contributions from leadership PACs, committees established by politicians that are funded in part by corporate PAC contributions.These loopholes allow corporate money to leak into these progressive campaigns, even if candidates take a “no-corporate-PAC” pledge, Billet said.

With these problems in mind, Presidential hopeful Elizabeth Warren denounced PAC contributions altogether. She still raised $6 million in her first quarter without taking a dime from PACs.

Presidential candidate Beto O’Rourke swore off all PAC money in his 2018 Senate bid too, but still raised $80 million in both small and large individual donations. He continues to avoid PAC money in his presidential run, raising more than $9 million this first quarter.

Will a rejection of corporate PAC dollars make or break a candidate’s chance of winning?

PAC money usually makes up a smaller proportion of overall campaign donations. In the 2018 midterm election, PACs contributed about $514 million to Republican and Democrat congressional candidates while individual donors gave $1.8 billion.

But to Billet, the Democrats’ tactic to rely on small-dollar donations may not be realistic.

“We assume that there will be enough money there, that folks will come forward and give the money,” he said. “But that still may not be enough.”

Money remains an influential factor in campaign outcomes. Nearly 90 percent of top spenders in 2018 House races claimed victory in their campaigns. And more than 85 percent of top spenders in Senate races won.

Jessica Levinson, the director of Loyola Law School’s Public Service Institute in Los Angeles, pointed to the potential consequences for candidates who swear off this stream of campaign money.

“[Candidates] are not as well-funded and they are fighting a campaign with one hand behind their back,” she said.

But no-corporate-PAC Democrats raised a treasure trove of cash in 2018 without accepting funds from PACs, a trend they hope to accelerate. And the positive media attention and voter trust that results from this pledge might also mean the benefits outweigh the losses — that is, if they can keep their promise.

“I have a strong feeling that the candidates have made that calculation,” Levinson said. “It’s a big political winner to say they are not beholden to PACs.”