Turning Point – The Future of the United States in the Greater Middle East

“All is well! Missiles launched from Iran at two military bases located in Iraq. Assessment of casualties & damages taking place now. So far, so good! We have the most powerful and well equipped military anywhere in the world, by far! I will be making a statement tomorrow morning.”

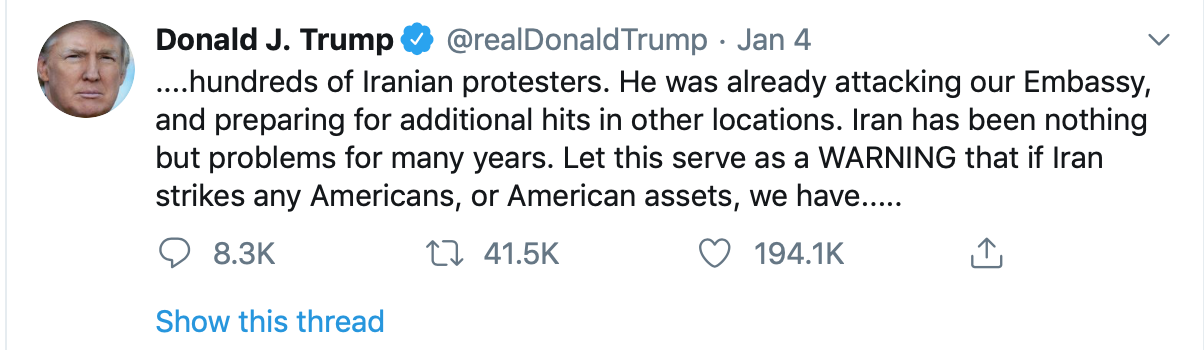

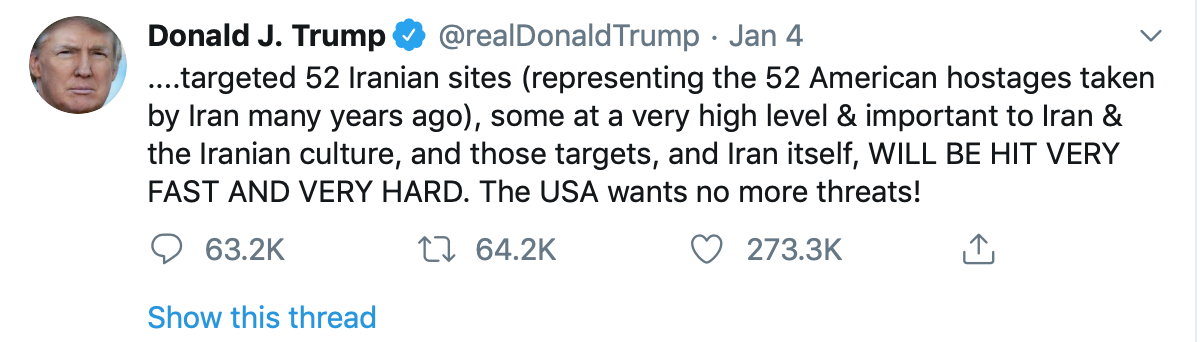

Taking to Twitter at the height of Iran’s retaliatory airstrike against several U.S. military bases in Iraq in the early hours of January 8, 2o20, U.S. President Donald Trump’s tone was oddly conciliatory, in sharp contrast with previous threats that Iran would face cultural obliteration should it dare offer a response to the assassination of its most senior military commander: General Qassem Soleimani.

Gen. Soleimani, the revered Commander in Chief of the Iranian’s elite Quds Units was killed in a U.S. airstrike on January 3rd near Iraq’s capital city, Baghdad, as he led a diplomatic mission aimed at brokering peace between the Islamic Republic and Saudi Arabia.

Iraq caretaker prime minister, Adil Abdul Mahdi, made it clear in an address to the press on January 4th that General Soleimani was there in an official quality, at Baghdad’s express invitation. “I was supposed to meet him in the morning the day he was killed, he came to deliver a message from Iran in response to the message we had delivered from the Saudis to Iran.”

Sources in Iran have speculated that Trump used his Office “to lure the General in a trap to take him out,” a move they warned will seal America’s fate in West Asia.

However one wishes to rationalize Trump’s administration decision to order the death of a foreign state official, America committed a war crime, which, under international law constitutes a serious breach of all legal norms, and therefore sets a dangerous precedent.

Speaking to Democracy Now, Col. Lawrence Wilkerson, who served as Secretary of State Colin Powell’s chief of staff from 2002 to 2005 notes: “We have just, as we did with torture from 2002 to 2007, 2008, as we substantiated for the world that torture was OK, we have now OK’d the killing of recognized members of other states’ government. That’s what Soleimani was, no matter how heinous we may paint him. He was a member of an established state’s government, and we assassinated him. That is a very dangerous precedent to have set.”

And, “We have become the law of the jungle, rather than, as we have been since 1945, the greatest supporter of international law and the rule of law in general across the face of the globe.”

While it is unlikely the U.S. will face any real legal fallouts – except for a few meek condemnations – the international community’s overall response to General Soleimani’s death has been rather muted. America’s geopolitical gravitas in West Asia may soon prove to be naught – and there may lie America’s biggest miscalculation.

As we may soon find out, the death of Iran’s military strongman could not only precipitate U.S. military withdrawal from Iraq but hamper Washington’s ability to lean on West Asia through its tight network of military alliances and political patronage.

Unpacking Iran’s Attack of US Interests in Iraq

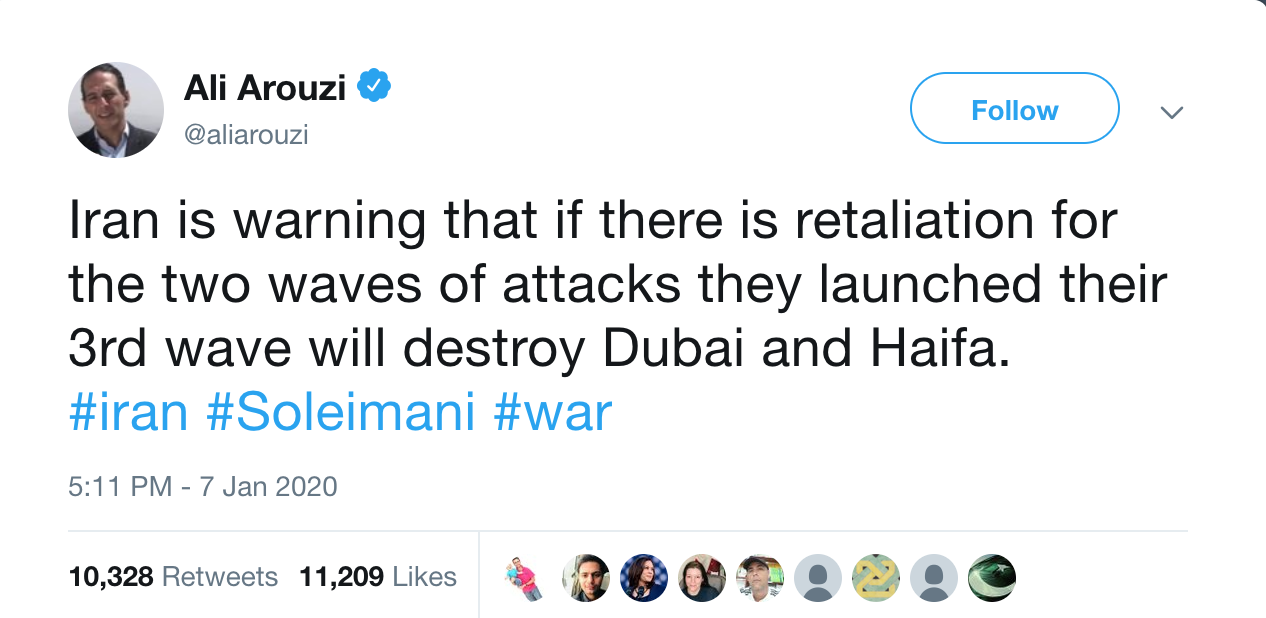

Iran’s barrage of missiles this Wednesday against the U.S. military and the many and grave threats Tehran leveled at neighboring countries – namely Israel and the United Arab Emirates – marked a historical turning point in the geopolitical balance of the region. It also raised some serious questions as to Washington’s real commitment to its partners in the region. In the face of Iran’s direct threats against both Israel and the U.A.E., the White House kept uncharacteristically mum.

If today many experts argue that President Trump exercised restraint, one must admit that such restraint runs a little contrary to the usual narrative. It may be a sign that Washington may not be as keen to rescue its allies from any and all threats, should they, in fact, find themselves in need.

Wednesday’s presidential address did nothing by way of reassurance either, since no mention was made of the Islamic Republic’s almost declaration of war on two of its regional neighbors.

Could it be that Trump’s promises of military support to its allies only run skin deep? In which case, could we see a situation where middle eastern countries will strive to look elsewhere to secure their sovereignty and guarantee the longevity of their institutions?

But then again Mr. Trump did run his presidential campaign on the promise that he would disengage from the region, and end “ungrateful” U.S. partners’ abuses of America’s military and financial largess. The writing may have been on the wall all along.

In hindsight, President Trump did make his intentions clear. Back in October 2019, he, after all, ordered the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Syria noting, “Let someone else fight over this long-bloodstained sand…” The United States has done a “great service” and “great job” for Turkey, Syria, and the Kurds by engineering a pause in their perpetual fighting, he argued, “and now we’re getting out.”

As Foreign Policy wrote in October 2019, “It has become increasingly clear that the U.S. government has neither the political resolve nor the capability for prolonged military action in the Middle East.”

And, “President Donald Trump’s White House has made clear its intent to reduce the U.S. military footprint in Syria and Afghanistan. Moreover, even as Trump has incrementally increased the U.S. troop presence in the Persian Gulf, his bullying and bluster have reinforced perceptions of the United States as an unreliable partner and accelerated a global rebalancing away from U.S.-led economic and security initiatives.”

As far as this administration is concerned the Middle East might no longer be a worthy investment. “We have avoided another costly military intervention that could’ve led to disastrous, far-reaching consequences,” Trump said of his decision not to oppose the incursion by Turkey into Syria back in late 2019. “We have spent $8 trillion on wars in the Middle East … But after all that money was spent and all of those lives lost, the young men and women gravely wounded—so many—the Middle East is less safe, less stable, and less secure than before these conflicts began.”

To America’s new nonchalance one needs to add the lack of a common vision between Washington and its fellow western capitals. Perhaps, more pressing have been the internal issues western capitals have had to grapple with – Britain’s Brexit, France’s Yellow Vests – somewhat putting matters of hegemonic expansion in the Middle East on the back-burner.

With the United States on the way out new players such as China and Russia will compete for influence.

As the dust settles on Iraq’s exploded military bases, we may soon wake-up to an entirely new Middle East, with all the uncertainty it entails.