How Mexico is Reforming its Immigration Process

“There’s a lot of talk about looking for alternatives, but the detention centers are full, the massive operations continue … they separate families and even a child lost her life.”

The Mexican immigration agency is creating new shelter options for asylum seekers and migrants who have experienced dangerous conditions, extortion, and abuse throughout the nation’s overfilled detention centers.

In the process, immigration officers are relocating a makeshift camp of over 1,000 migrants from outside a detention center in Tapachula, at the border with Guatemala.

Young migrants from Honduras gather in a Mexico City stadium, where temporary migrant housing was established in November 2018. (Photo: Jenna Mulligan)

Mexico continues to experience a constant influx of migrants traveling through southern states and, often, continuing toward the U.S.-Mexico border.

Some of this migrant population is from the neighboring Central American countries of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. But Mexico, for years, has received cyclical migrations of individuals from Haiti, Cuba, and as far away as Cameroon and the Congo. Now, these regional and intercontinental migrants are joining the path of caravans which have traversed Mexico consistently over the last six months, bound for the U.S. border where they plan to claim asylum.

Mexican immigration officials, under pressure from their northern neighbors, have increased their deportations by 150 percent in 2019.

? El @INAMI_mx informa que en coordinación con autoridades consulares de #Honduras, se realizó un segundo vuelo para retornar a su país a 109 hondureños, la mayoría familias con niños, todos en condición de estancia irregular en #México. pic.twitter.com/cZiXHl75ZB

— INM (@INAMI_mx) May 24, 2019

Human Rights Violations at the Detention Centers

President Trump consistently threatens Mexico to detain and deter more of the migrant population, but Human Rights Watch is demanding reforms in officer conduct and living conditions in the detention centers, where many children are kept as they await deportation or apply for asylum with their families.

Five small detention centers were closed in late February, and about 50 centers remain in operation. The closures occurred in southern Guerrero, Veracruz, northern Michoacán, and in Nogales, on the border with Arizona. The center in Reynosa near McAllen, Texas was also closed and the director was fired after a broadcast news agency reported that officials were extorting the migrants held there for money.

Tonatiuh Guillén, the Director of the National Immigration Institute in Mexico, recognized that the structure and conduct of detention centers in the country were unsuitable for children.

“The (detention centers) have a very severe conduct model and from the perspective of children, it’s completely inappropriate,” Guillén told the Associated Press.

A 10-year-old Guatemalan girl died on May 15 in Mexican immigration custody, after falling from a bunk bed in the Iztapalapa Migration Station.

Authorities apprehended the girl with her mother in the northern state of Chihuahua. They returned to Mexico City, where they were sent to the detention center to await deportation proceedings. Mexican officials confirmed the death, but did not reveal details of the trauma which caused the fatality until the following day.

Original reports cited a sore throat as the cause for her trip to the hospital. As a result, the incident is under investigation by authorities and human rights groups.

Mexican Immigration Authorities Look for Internal Reform

“There’s a lot of talk about looking for alternatives, but the detention centers are full, the massive operations continue … they separate families and even a child lost her life,” said Ana Saiz, Director of migration-focused NGO Sin Fronteras.

Guillén maintains that no families are separated, but the National Immigration Institute recently fired 600 employees for signs of corruption and poor conduct.

“This government needs to urgently move from words to deeds,” Saiz told the AP.

According to Guillén, the National Immigration Institute will address the insufficient facilities by designing and constructing a migrant shelter on a 37-acre lot in Chiapas in late 2019.

The new shelter proposed by the Institute would be available to those requesting asylum in Mexico, and those with regional work permits. Individuals would be free to come and go as they please, rather than living in detention cells. This would also free up space in detention centers for individuals being deported by Mexican authorities.

On Tuesday night, authorities proceeded to relocate over 1,000 migrants from parks and makeshift camps in Chiapas border cities to a fairgrounds space, possibly the lot for this shelter.

Tension in Tapachula

The proposed facility would be in Tapachula, Chiapas, where 1,300 migrants broke out of the Siglo XII detention center in late April. The majority of migrants held at this facility are Cuban, and about 600 of those who fled the center did not return.

In early May, a group of 90 attempting another escape, but were unsuccessful.

Unrest has grown in this region of Mexico as the threat of deportation increases, and backlog in the immigration procedures leads to months of waiting in the Chiapas border city.

Much of the recent tension has involved the growing Cuban population among the thousands of migrants in transit.

On March 15, about 500 Cubans stormed the Mexican immigration office which issues exit visas. Without the visa, individuals are unable to leave the city legally, subject to deportation from Mexico.

As a result of the protest, the immigration office shut down for nearly two months, reopening on May 6.

Now, the wait list for exit visas is run by a fellow migrant, similar to the wait lists compiled in northern Mexico border cities such as Tijuana.

“Can’t you see from our faces just how desperate we are,” said Javier Valdez, who volunteered to oversee the list, which quickly grew to almost 1,500 names. “Some people I know have been in Tapachula for two months.”

Many of the undocumented Cuban migrants in Chiapas are skilled workers with upper-education degrees. But if deported back to Cuba, they say these degrees won’t help them find work with a living wage.

María Janes Rodríguez, who worked as a nurse in Cuba for $30 a month, is now 1,206th on the list for an exit visa.

“I can’t go back there … I sold all my things,” Rodríguez said. “What would I go back to? I’m terrified of being deported from Mexico. There’s no freedom in Cuba.”

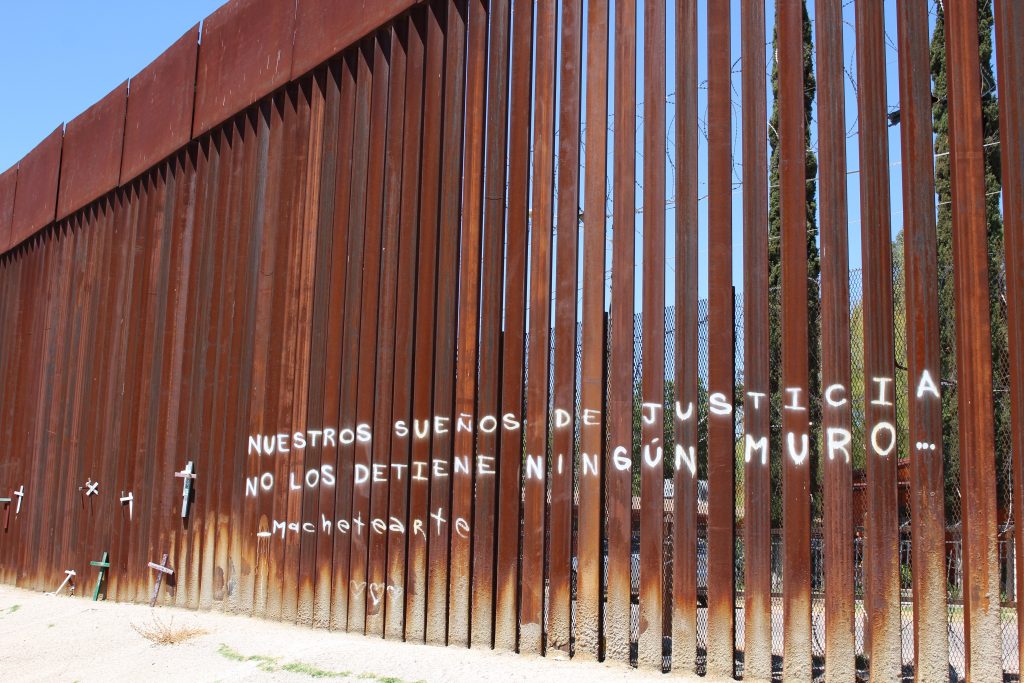

Words painted on the border wall in Nogales, Mexico read “Our dreams of justice will not be deterred by any wall.” (Photo: Jenna Mulligan)