How to Legalize Ecstasy — And Why

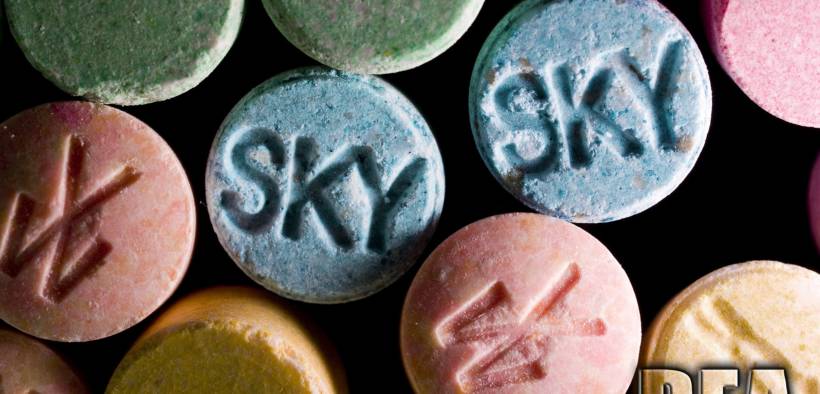

The most serious harmful effect of treating ecstasy use and sales as a criminal matter is that users are forced into an unregulated, no-quality-control black market, and they don’t know what they’re getting.

Every weekend, hundreds of thousands of young club- and concert-goers buy and consume black-market pills and powders they hope are MDMA, the methamphetamine relative with a psychedelic tinge known on the streets as ecstasy or molly. A tiny, tiny percentage of them—a few dozen each year in the United States or Britain—die. It doesn’t have to be that way.

Granted, those numbers are minuscule when compared with the tens of thousands who die each year in the U.S. using opioids, benzos, and stimulants like cocaine and meth, but that relative handful of deaths could almost certainly be eliminated by bringing ecstasy in from the cold—making it legal and regulated instead of subjecting its users to black-market Russian roulette.

And now somebody—not Sen. Elizabeth Warren—has a plan for that. The British Beckley Foundation, which has been advocating for research into psychoactive substance and evidence-based drug policy reform for the past two decades, has just released a new report, Roadmaps to Regulation: MDMA, that takes a good, hard look at the drug and charts a path to a saner, less harmful way of handling ecstasy than just prohibiting it, which, the report notes, “has never meaningfully disrupted its supply, nor its widespread use.”

That’s because, despite its being illegal, for many, many people, ecstasy is fun. And the Beckley report does something rare in the annals of drug policy wonkery: it acknowledges that. “Hundreds of thousands of people break the law to access its effects, which include increased energy, euphoria, and enhanced sociability,” the report says.

The authors concede that ecstasy is not a harmless substance, and take a detailed dive into acute, sub-acute, and chronic harms related to its use. They point to overheating (hyperthermia) and excess water intake (hyponatremia) as the cause of most ecstasy deaths, and they examine the debate over neurotoxicity associated with the drug, very carefully pointing out that “there is evidence to suggest that heavy use of MDMA may contribute to temporary impairments in neuropsychological functions.”

But they also point out that most of the problems with ecstasy are artifacts of prohibition: “Our evidence shows that many harms associated with MDMA use arise from its unregulated status as an illegal drug, and that any risks inherent to MDMA could be more effectively mitigated within a legally regulated market,” they write.

The most serious harmful effect of treating ecstasy use and sales as a criminal matter is that users are forced into an unregulated, no-quality-control black market, and they don’t know what they’re getting. Tablets have been found with as little as 20 milligrams of MDMA and as much as 300 milligrams. And much of what is sold as MDMA is actually adulterated with other substances, including some much more lethal ones, such as PMA (paramethoxyamphetamine) and PMMA (paramethoxymethamphetamine). This is how people die. As the authors note:

“The variability in MDMA potency and purity is a direct result of global and national prohibitionist policies. Recent developments around in situ drug safety testing are an attempt to mitigate the risks of such variability. These risks, such as overdose and/or poisoning, are by no means inevitable or inherent to the drug. If MDMA were clinically produced and legally distributed, users would be assured of the product content and appropriate dosage, and be able to make more informed decisions regarding their MDMA use. In this way the principal risks we associate with MDMA use would be greatly reduced.”

But the report also addresses a whole litany of other prohibition-related harms around ecstasy that exacerbate the risks of its use. From making users less likely to seek medical help for fear of prosecution to making venues adopt “zero tolerance” policies that actually increase risks (such as drug dog searches that encourage users to take all their drugs at once before entering the venue) to the rejection of pill testing and other harm reduction measures, prohibition just makes matters worse.

In addition to harms exacerbated by prohibition, there are harms created by prohibition. These include “a lucrative illegal MDMA market that generates wealth for entrenched criminal organizations,” the saddling of young users with criminal records, the risk that people who share or sell drugs among their friends could be charged as drug dealers, and the development of black markets for new psychoactive substances (NPSes), many of which are more dangerous than ecstasy. Also not to be forgotten is the loss of decades of research opportunities into the therapeutic use of MDMA, research that was showing tremendous potential before the drug was prohibited in the mid-1980s.

The prohibition of ecstasy is not only not working but is making matters worse. So what should we do instead? The Beckley Foundation report is very clear in its conclusions and recommendations. First, these preliminary steps:

- Reschedule MDMA from Schedule I to Schedule II of the Controlled Substances Act (the Misuse of Drugs Regulations in Britain) in order to reduce barriers to research and to improve our understanding of its physiological effects.

- “Decriminalize the possession of MDMA and all drugs to remove the devastating social and economic effects of being criminalized for drug possession or limited social supply.”

- Use decriminalization to comprehensively roll out drug safety testing (pill testing) and other proven harm reduction measures.

Once those preliminary steps are done, it’s time to break big:

- Award licenses to selected pharmaceutical manufacturers to produce MDMA under strict manufacturing requirements.

- Allow licensed MDMA products to be sold at government licensed MDMA outlets. The report suggests pharmacies in the first instance.

- For harm reduction purposes, retail outlet staff would need to be specially trained to educate users on the risks associated with MDMA.

- Users who wish to purchase licensed MDMA products would be required to obtain a “personal license” to do so. Such a license would be granted after an interview with trained sales staff demonstrates that the would-be user understands the risks and how to reduce them.

- Develop adults-only MDMA-friendly spaces where the risks associated with the drug can be combatted with the full panoply of harm reduction measures.

- “User controls” to encourage responsible MDMA use. These would include “a strictly enforced age limit, pricing controls, mandated health information on packaging and at point of sale, childproof and tamperproof packaging, a comprehensive ban on marketing and advertising, and a campaign to minimize the social acceptability of driving under the influence of MDMA and to promote alternatives such as designated drivers.”

- “Sales of MDMA would be permitted to adults over 18 years of age. Prohibitive penalties would be in place to restrict underage sales.”

- Education campaigns focusing on MDMA safety and responsible use that would cover sales outlets and schools and universities. Such campaigns would include information about how to recognize and manage adverse events related to MDMA products.

- Monitor and evaluate the impact of these changes to continue an evidence-based approach and allow feedback into policymaking.

There you have it, a step-by-step plan to break with prohibitionist orthodoxy and create a legal, regulated market for a popular recreational drug. Whether you or I agree with every plank of the plan, it is indeed a roadmap to reform. The evidence is there; the plan is there. Now all we need is the political pressure to make it happen somewhere. It could be the United Kingdom, it could be the United States, it could be the Netherlands, but once somebody gets it done, the dam will begin to burst.

This article was produced by Drug Reporter, a project of the Independent Media Institute.