Unpacking and Understanding Media Bias: The Long History of Fake News

When ‘fake news’ has been a part of U.S. journalism since the days of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, is there any hope for modern-day journalism?

This is the eighth part in a Citizen Truth series on media bias and the history of the press, read the first parts below.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7

Despite the perception that fake news is a modern-day problem, in reality, both fake news and modern-day progressive social-reforming journalism have their roots planted firmly in the new journalism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

New Journalism and Truth

Commonly held assumptions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries regarding the existence and perceptibility of truth played a pivotal role in the development of new forms of journalism. Americans and journalists of the day originally found the basis of truth in religion, more specifically in Christianity. Regardless of denomination, doctrine or dogma, Christians shared a set of principles and the belief that a discernible biblical truth existed. As a whole, Americans rejected the idea of relativism.

It did not take long, however, for a chasm to form between religion and journalism, a divide widened by newspaper editors like William Randolph Hearst and self-proclaimed atheist E.W. Scripps, who displayed blatant hostility toward religiously oriented news. As religious and spiritual influence within the news industry waned, wire services filled the gaps by providing stories free of blatant bias and political partisanship. The succinctness of wire service reporting, together with the financial limitations of the publishing industry, established the dominance of fact-focused reporting just before the turn of the 20th century.

Social-Reforming “Muckrakers”

As American journalism progressed toward and through its era of objectivity, journalists began to operate and write in ways more conducive to their own values than those of their readers.

Specifically, social-reformer journalists of the day wanted journalism to look to the future, to what the country’s values should and would become. They sought to address what they saw as society’s ills and failures head-on. Similarly, and not surprisingly, they had great difficulty reporting good news regardless of the truth in it. Everything was an exposé, and they faced a predicament that only true and critical reporting fit the description of good journalism, when in reality the truth might require reporting without criticism.

Irritated by an article in one of Hearst’s magazines, Teddy Roosevelt labeled the most extreme of these reformers “muckrakers,” a term he borrowed from John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, in which characters used rakes to dig up filth and muck. Journalistic muckraking was digging up stories on the political and social elite, which did not hew to the values they held. Muckrakers operated under the assumption that values required challenging.

So, what if the public actually believed in the “right” values? Do those also require challenging? And who determines the right values? The journalists and their editors made those decisions.

Most muckrakers did not reach the levels of fame or popularity of high-profile journalists like Joseph Pulitzer, Hearst or Upton Sinclair; in fact, many were nothing more than sensationalists.

Pulitzer built his circulation on a combination of exposés, reform journalism and sensationalism, yellow journalism or fake news. His paper, the New York World tackled such issues as contaminated food, official misconduct and immigrant issues like tenement housing. In particular, Nelly Bly’s undercover reporting on a mental asylum for the indigent gained fame with the publishing of Ten Days in a Madhouse.

Little more than a decade later, Hearst attempted, quite successfully, to duplicate Pulitzer’s business model. In so doing, he became Pulitzer’s biggest competitor. Together, Pulitzer and Hearst represented a new form of journalism, sensationally written reform journalism.

The upper echelon of society and government detested Hearst and Pulitzer for their form of journalism, their politics and the class of their readership. As wealthy, self-made and uncontrollable men, the elite hated them all the more for their pointedly Democratic views in a time when elites and most of the press belonged to the Republican party.

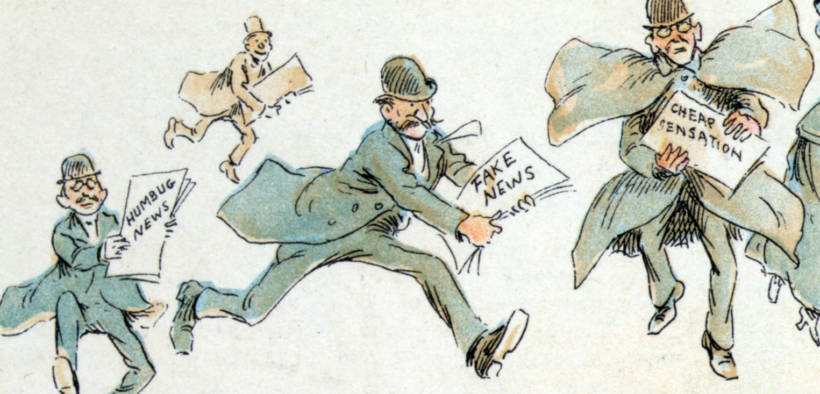

Sensationalism, Fake News and Yellow Journalists

In complete contradiction to the façade of progression toward fact-based reporting in the mid-to-late 1800s, the demand to fill columns in newspapers often led reporters and editors, including Hearst and Pulitzer, to fabricate stories on days lacking enough actual news to fill the paper. This sometimes proved detrimental to newspapers as competitors could easily contradict fake news. Many editors of the day actually disdained sensationalized journalism, also known as yellow journalism, and the associated drive for scandal and crime.

The primary purpose of yellow journalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was merely to sell papers. It referenced fake interviews or details from unnamed sources and employed pseudoscience and false information in its attempts to sway readers. If this sounds at all familiar, it should, as the citing of unnamed sources and pseudoscience have become exceedingly common habits in modern-day journalism as well.

While it is true both historically and contemporaneously that some fake news is easily identified, some is far more insidious and exceptionally more difficult to identify. Threads of truth woven together with untruths and half-truths are presented in ways that make them seem totally plausible. Only by fact-checking such stories would anyone even know they are not accurate. With very few people taking the time to read beyond the headline or first paragraph, it is understandable that much of the contemporary American public is so easily misled.

News media everywhere in the world are guilty of cover-ups and political propaganda. That includes all American mainstream media (including PBS), as well as the BBC and Reuters, but the media of other countries are similarly culpable.

As Mark Twain long ago observed: “If you don’t read the newspaper, you are uninformed. If you read the newspaper, you are misinformed [and disinformed].”

There are some objective investigative journalists that do very good work, but by and large they are lost in the shuffle. Journalism schools are woefully lacking in something quite crucial: teaching you to how to know and truly understand what you are talking about, and having the guts to write and say it.